The World's Healthiest Foods are health-promoting foods that can change your life.

The World's Healthiest Foods are health-promoting foods that can change your life.

Try our exciting new WHFoods Meal Plan.

The World's Healthiest Foods are health-promoting foods that can change your life.

The World's Healthiest Foods are health-promoting foods that can change your life.

Try our exciting new WHFoods Meal Plan.

Yes, dinner size matters! And it's not just the size of your dinner but also the timing and the foods you select that can impact your health. As the last meal of the day, dinner plays a unique role in healthy eating, and we think you might be surprised at some of the research findings related to this most widely eaten meal in the United States.

On a nationwide basis, 85% of U.S. adults eat something for breakfast, 81% eat something for lunch, and 93% eat something for dinner. While these percentages favor dinner, they are all relatively high and somewhat close. However, when these three meals are evaluated in terms of calories, their differences become much greater. Adults in the U.S. consume two times more calories (34% of total calories) at dinner than at breakfast (17%). And these dinner calories are still 10% higher than calories at lunch (24%). Put somewhat differently, among all meal-time calories, 45% are provided by dinner. Dinner is by far the major meal of the day for U.S. adults in terms of calories.

Research studies show two very different cultural trends that seem to run at cross purposes with respect to dinner. On the one hand, dinner is a time when we can be together with friends and family, taking time to enjoy a genuine meal. On the other hand, dinner comes later in the day when we might be tired from the day's work, not looking forward to food preparation and clean up, or unusually hungry from skipped meals.

These two themes—the stressful aspects of dinner versus the opportunities that it can provide us for sociability and enjoyment—have made for some interesting research results about this meal. If your dinner becomes a time where the stresses of your day take over, the result is increased risk of overeating. For example, overtime work that pushes your dinner late into the evening (typically after 9pm) also brings with it overconsumption of food. Similarly, the practice of having dinner within two hours of bedtime at least three days per week has been linked to overeating and higher body mass index (BMI). If breakfast is also skipped on the mornings after a late dinner, these links become even stronger and place you at even more risk. Finally, as the timing of your dinner gets increasingly postponed between 7pm and 10pm, your risk of overeating will increase proportionally and so will your calorie intake. So, the bottom line is this: if the stresses of your day compromise the quality of your dinner, or if you push dinnertime off too late into the evening, you increase your chances of eating more than you planned and you are likely to compromise your health rather than optimizing it.

At WHFoods, our goal is to provide you with all of the food tips, kitchen tips, and recipes need to enjoy a nutrient-rich, delicious dinner. We want dinner to fit perfectly into your day! Along these lines, we noticed that in one research study, participants estimated that they would need 80 minutes of time to prepare and consume a home-cooked dinner. While some of our website and cookbook recipes do indeed require this amount of time, we provide you far more often with recipes that can be prepared and cooked with 20 minutes!

For us, healthy eating and nutrient-rich cooking should never be steps that will interfere with your enjoyment of dinner! In fact, we are confident that our healthy eating and nutrient-rich cooking steps can make your dinner meal a great fit. We would also note that consistency counts! Multiple research studies show that consistency with the timing, size, and composition of your dinner meals can work in your favor by giving your metabolism a reliable context for balancing food intake with hormone levels, cell activities, and other factors.

Some of the most fascinating research about dinner involves its relationship to bedtime (and sleep). While the details from this research are complicated, the basic principles are fairly simple. If you want to be healthy, your body must adapt to the natural pattern of day and night. Many aspects of your metabolism follow this day/night pattern. For example, one of the key hunger-related hormones (ghrelin) that is released by your stomach peaks during the day (about 1pm) and begins to decline from 4pm onward. By contrast, leptin—a messaging molecule that gets released from your fat cells and is associated with satiety or sense of fullness—tends to decline during the day (from 8am to 4pm) and to increase from 4pm onward. Both of these patterns are consistent with a need for greater food intake during the day and less food intake in the evening. Your body cannot ignore these natural patterns in metabolism that keep you adapted to the cycle of day and night.

If you eat in a way that runs contrary to these natural metabolic patterns, you make it more difficult for your body to adapt and get in sync with the natural pattern of day and night. Skipping meals during the day would be an example of an out-of-sync eating approach. So would consumption of a large meal late in the evening. Recent studies on adiponectin—a messaging-molecule-like leptin that gets produced by our fat cells—have shown the unwanted impact of eating habits that are out-of-sync with natural day/night cycles. Late-night eating and the skipping of daytime meals have each been linked to unwanted fluctuations in adiponectin levels, and these altered adiponectin levels have been associated with increased risk of obesity, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome.

Research findings in this area continue to be intriguing and mixed. At least one study has shown the ability of a carb-focused dinner to alter hormonal balances on the following day, and to potentially help prevent mid-day hunger in individuals who are obese and have excessive amounts of body fat. There is some evidence that substantial intake of fats at breakfast can help promote better fat metabolism throughout the day, and this observation has encouraged some researchers to recommend a relative emphasis on fat intake earlier in the day and a relative emphasis on carb intake later on.

It's interesting to note that in some countries (for example, France), there is often more emphasis on fruits at dinner than in the U.S. One study that we reviewed showed over six times as much fruit consumption at dinner among families in France than in U.S. families. This fruit example would fit well into the "carbs at dinner" approach since fruits are generally high in carbohydrates and very low in fat.

However, the issue of carbs versus fats at dinner is complicated by many other issues. One example is the issue of insulin responsiveness. For most individuals, insulin responsiveness is lower in the evening hours, making it more difficult for the body to juggle the impact of a high-carb meal. At the same time, however, too much fat intake at dinner raises questions about the timing of digestion and sleep, since dietary fat requires much longer period of digestion than dietary carbohydrate. Too much fat intake at dinner can result in too little digestive time between this final meal time and bedtime.

In summary, we have been unable to find a clear research trend in this area, and for that reason, have stuck with our basic approach to carbs and fats for all three daily meals—including dinner. As a general rule, our meal plans tend to have more fats at dinner than at breakfast, but all of our meals contain a substantial amount of fat, including our breakfasts. At the same time, our overall carbs tend to be on the lower side (about 45% of calories), and our overall fats tend to be on the higher side (about 35% of calories). So, we do not typically have any high-carb meals (including dinner), but we do often have higher-fat meals (including both breakfast and dinner). It's not unusual to find WHFoods breakfasts or dinners that contain 25 grams of fat. We have found that these higher fat levels seem to work well at both breakfast and dinner, provided that the size of each meal is kept in a reasonable proportion and that dinner is eaten relatively early in the evening and fully enjoyed as a special meal.

As we have already described, dinners tend to be the largest meals in our meal plans. We realize that this eating approach is not for everyone, and we encourage you to approach dinner in a way that makes the most sense for you and your lifestyle. At the same time however, we believe that for many people, a relaxed, family-type meal is often not possible except at dinnertime, and we believe that the shared enjoyment of a meal can be one of the day's most meaningful events. In the U.S., more people eat dinner than any other meal. So in a practical sense, dinner provides a special opportunity in our U.S. way of eating.

At the same time, we do not recommend that anyone abandon basic eating principles at dinner, including principles related to portion size. Nor do we recommend late meals that push dinnertime too close to bedtime. The relatively large size of our dinners at WHFoods makes the timing of this last meal more important than end-of-the-day eating in a meal plan where breakfast or lunch function as the main meal. For this reason, we recommend that dinner be enjoyed relatively early in the evening. Healthy eating and nutrient-rich cooking can be accomplished within many different types of meal plans. Regardless of the way that dinner fits into your meal plan, we encourage you to

take advantage of our food tips, kitchen tips, and recipes to create a last meal of the day that works for you in terms of practicality, personal enjoyment, and health benefits.

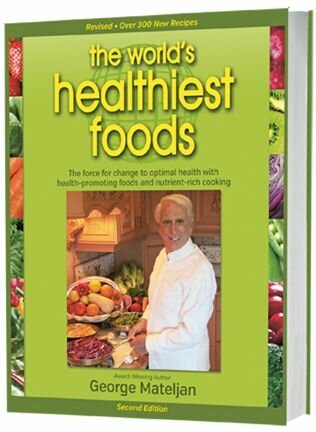

Everything you want to know about healthy eating and cooking from our new book.

Order this Incredible 2nd Edition at the same low price of $39.95 and also get 2 FREE gifts valued at $51.95. Read more